- Visibility 33 Views

- Downloads 4 Downloads

- DOI 10.18231/j.ijpns.2021.001

-

CrossMark

- Citation

Study of febrile seizures among children admitted in a tertiary care hospital

- Author Details:

-

Pradeep G C *

-

Saritha H M

Introduction

Febrile seizures are generally defined as seizures occurring in children typically 6 months to 5 years of age in association with a fever greater than 38°C (100.4°F), who do not have evidence of an intracranial cause (e.g. infection, head trauma, and epilepsy), another definable cause of seizure (e.g. electrolyte imbalance, hypoglycemia, drug use, or drug withdrawal), or a history of an a febrile seizure. [1], [2], [3], [4], [5] Febrile seizure is a major challenge in pediatric practice because of its high incidence in young children and its tendency to recur. In recent years, there has been more awareness about the potential complications of febrile seizures and management of this condition. Updated guidelines for the evaluation and management of febrile seizures were published by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the Japanese Society of Child Neurology in 2011 and 2015, respectively.[6], [7] This article provides an update on current knowledge about febrile seizures and outlines an approach to their evaluation and management.

Febrile seizures are the most common paroxysmal episode during childhood, affecting up to one in 10 children. They are a major cause of emergency facility visits and a source of family distress and anxiety. Their etiology and pathophysiological pathways are being understood better over time; however, there is still more to learn. Genetic predisposition is thought to be a major contributor. Febrile seizures have been historically classified as benign; however, many emerging febrile seizure syndromes behave differently. The way in which human knowledge has evolved over the years in regard to febrile seizures has not been dealt with in depth in the current literature, up to our current knowledge.

Simple FS have an age range classically described as 6 to 60 months. The peak incidence is usually in the second year of life. FS are prevalent in up to 5% of children, with the overall incidence estimated to be 460/100,000 in the age group of 0-4 years. Most FS are simple; however, up to 30% might have some complex features. The risk of recurrence of FS is related to various factors, including a younger age group, prolonged seizure duration, degree of fever, and positive personal and family history of FS. In fact, a positive family history of FS in first-degree relatives is observed in up to 40% of patients. Gender distribution has been studied in the literature. One previous study found a mild male predominance but this has not been supported by other literature reviews. The underlying pathophysiological explanations for these observations remain obscure.

Objectives of the study

The objectives of this study were to evaluate the clinical profile, investigations, course in hospital, and out come of children admitted with febrile seizures.

Materials and Method

Source of data:The study was done on cases admitted in Pediatric ward or intensive care unit of Bangalore Baptist Hospital a tertiary care centre, Bangalore from January 2018 to august 2019.To know the clinical profile investigation and course and outcome of febrile seizures admitted in hospital.

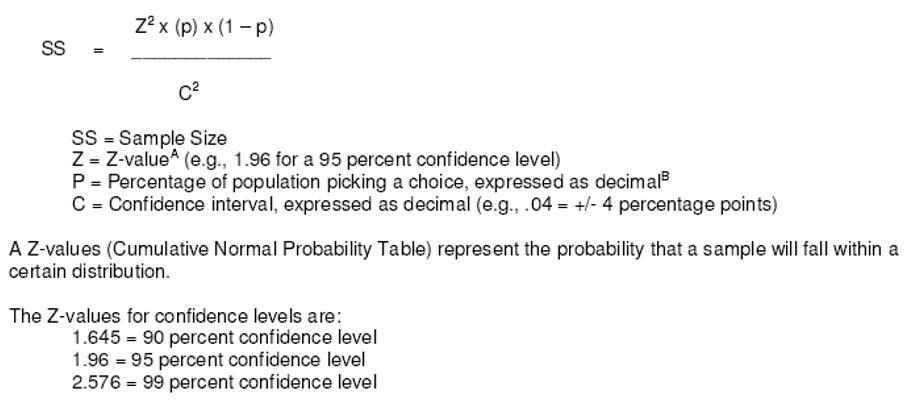

Sample size

Data collection technique and tools

Data were collected regarding socio-demographic characteristics, child’s illness, neonatal history, developmental milestone and family history of FSs or epilepsy. Weight and height were recorded and full neurological examination was done and the axillary temperature was taken for all patients at the time of admission.

Investigation

Data were collected regarding socio-demographic characteristics, child’s illness, neonatal history, developmental milestone and family history of FSs or epilepsy. Weight and height were recorded and full neurological examination was done and the axillary temperature was taken for all patients at the time of admission. CBC was done for all patients and PCV values.

Inclusion criteria

Children from 6 months to 6 years of age presented with fever with seizures without central nervous system infection.

Exclusion criteria

Children less than 6 months or more then 6yrs

Children with neurological disorders

Method of statistical analysis

Statistical analysis Data were presented in frequency, percentage, mean, standard deviation and odd ratio. The odd ratio is a measurement of risk of certain factors with its 95% confidence interval for the accurate range of risk. The student test (t-test) and chi-square test were used for the significant testing with a p valueas the level of significance.

Results

There were 112 children which constituted 7.2% of total Paediatric admissions, were matched to 112 control febrile patients without seizure with the same age range, who admitted the same hospital during the same period of time. There were 68(60.7%) males and 44(39.2%) females. The duration of hospitalization ranged between 1 and 14 days (mean = 5.2and SD = 4.2). 25 children (22.32%) had history of a febrile seizure and 32 (28.5%) had positive family history of febrile seizures. 80 childern had simple febrile seizures (71.4%). 22 had complex febrile seizures (19.6%) and10 febrile status (8.9%)

|

Age of the patients |

No. of cases in the particular age group |

|

6–12 months |

28 cases (25%) |

|

12–24 months |

51 cases (45.5%) |

|

2–5 years |

21 cases (18.75%) |

|

More than 5 years 2 cases |

12 (10.7%) |

|

Duration of hospitalization |

Total no.of days of hospital stay |

|

No. of cases 1–2 days |

80 cases |

|

3–5 day |

20 cases |

|

6–10 days |

10 cases |

|

More than 10 days |

2 cases |

The mean age and standard deviation for cases were 25.8±15.19 months and for control was 29.9±18.5 months. This was statistically not significant (p-value >0.05). Seventy seven percent of cases had febrile seizures for the first time and 22.3% had recurrent febrile seizures. The mean age and standard deviation for the first febrile seizures were 23.54±12.8 months and recurrent febrile seizures were 29.83±12.5 months. This was statistically not significant (p value >0.05). The majority of the cases were between 12 -24 months with a peak at the age of 18-19 months. Of the characteristics studied, only the mean of temperature found to have a highly statistically significant difference between cases and control (p-value = 0.0001). Furthermore, cases with recurrent febrile seizures have statistically significant lower temperature than those with first febrile seizure (p-value = 0.0001)

|

Variable |

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

T test |

P value |

|

Age (months) |

25.80 |

15.95 |

29.99 |

18.50 |

1.715 |

0.088 |

|

Age of first FS |

23.54 |

12.8 |

|

|

|

>0.05 |

|

Age of recurrent FS |

29.83 |

12.5 |

|

|

|

>0.05 |

|

Tempon a dmission |

39.2 |

0.7 |

38.90 |

0.49 |

|

0.0001 |

|

Temp of first FS |

39.75 |

0.1 |

|

|

|

0.0001 |

|

Temperature of recurrent FS |

38.24 |

0.45 |

|

|

|

0.0001 |

The source of the febrile illness was evident in 70%, mostly resulting from upper respiratory tract infection followed by acute gastroenteritis. Investigations performed most commonly included CBC and serum electrolytes. CBC showed abnormalities suggestive of an infection in 48% cases. 58 cases were anemic. Lumbar puncture was performed in those who demonstrated signs of meningeal irritation or those who were younger than 1years of age (78.57%). Only one child had a positive cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) culture confirming meningitis. An EEG was performed on 22(19.6%) children with complex febrile seizures and febrile status, which were normal in 16 or showed minor nonspecific changes in 6. Obtaining an EEG was less likely in case of simple febrile seizures (13%vs.50% in atypical, P=0.002). However, EEG abnormality did not correlate with the seizure type.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain was performed in 12(10.71%) children and was normal in 9 cases. Two abnormal scans showed mild brain edema in one case and tuberculoma in the second.

Discussion

In the present study, the majority of cases of febrile seizure occur in the second year of life, peaking at 18-19 months. This is in agreement with the results of other studies. 9-11 febrile seizure are age-dependent and this age should be regarded as critical for developing febrile seizure. The mean age for those with first febrile seizure was 23.5 months; this figure is similar to that found by Ploch of 22.5 months. Males account for 60.7% of cases with a male to female ratio of 1.54:1. The male sex predominant is well documented in almost all series. There was no satisfactory explanation for this sex predominant. Study reveals that children with recurrent febrile seizures have a lower temperature at presentation than those with first febrile seizures. 28.5% of our cases were found to have a family history of febrile seizure and when compared with controls were found to be of statistical significance (p value=0.0007). This finding is in agreement with those studies that showed strong evidence of positive family history as a risk factor for febrile seizure. Furthermore, a family history of epilepsy was also found to be a risk factor for febrile seizure (p value 0.026).

A CBC and serum electrolytes were performed on all children. Both were not clinically very helpful, however, an abnormally high white blood cell (WBC) count resulted in increased exposure to IV antibiotics unnecessarily (the high WBC count is most likely seizure related). Other investigators also found a low yield of such investigations. An EEG was performed selectively on one-third of our children, mostly those with atypical febrile seizures, which did not yield any significant abnormality in most cases. MRI brain was performed in 12 (10.7%) children and was normal in 9 cases. Two abnormal scans showed mild brain edema in one case and tuberculoma in the second, however, no focal lesions were identified. The current American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommendations recommend that neuroimaging must not be performed routinely in febrile seizures.

Conclusions

The simple febrile seizure was the most common type of febrile seizure and febrile seizure predominantly affected children below three years of age. The first episode of febrile seizure occurred in the majority in the age group of 12 to 24 months age group. Recurrence of febrile seizure was common and was significantly associated with the age of the first episode at one year or below. Hence it is recommended that parents of patients with the first episode of a febrile seizure occurring at an age of one year or below should be appropriately counselled regarding seizure recurrence and measures during seizure activity as well as benign nature of the illness; which might reduce parental anxiety during further episodes of febrile seizure.

It was observed that children with simple febrile seizures are often selective admitted. The cases admitted frequently had a good reason for admission. However, the yield of investigations remains low and does not justify extensive work-up or prolonged hospitalization.

Source of Funding

None.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

- C C Huang, S T Wang, Y C Chang, M C Huang, Y C Chi, J J Tsai. Risk factors for a first febrile convulsion in children: a population study in southern Taiwan. Epilepsia 1999. [Google Scholar]

- H Doose, A Maurer. Seizure risk in offspring of individuals with a history of febrile convulsions. Eur J Pediatr 1997. [Google Scholar]

- S L Kugler, W G Johnson. Genetics of the febrile seizure susceptibility trait. Brain Dev 1998. [Google Scholar]

- F Zhao, S Emoto, L Lavine, K Nelson, C Wang, S Li. Risk factors for febrile seizures in the People's Republic of China: a case control study. J inte leage against epelipsy 1991. [Google Scholar]

- A Pisacane, R Sansone, N Impagliazzo, A Coppola, P Rolando, A D Apuzzo. Iron deficiency anaemia and febrile convulsions: case-control study in children under 2 years. BMJ 1996. [Google Scholar]

- P B McLntyre, S V Cray, J C Vance. Unsuspected bacterial infections in febrile convulsions. Med J Aust 1990. [Google Scholar]

- J L Trainor, L C Hampers, S E Krug, R Listernick. Children with first-time simple febrile seizures are at low risk of serious bacterial illness. Acad Emerg Med 2001. [Google Scholar]